Artists & Scientists

Click the thumbnails below to navigate and find out more about the artist-scientist pairs responsible for the projects shown in the Synergy Experience exhibitions.

Laurie & Jennifer

Keith & Suzanna

Deb, Svenja, & Caroline

Kathy & Chrissy

Hong & Caroline

Marcy & Sujata

Ellen & Larry

Janine & Jing

Heather & Noah

Saberah & Max

Claire & Nina

Cynthia & Michelle

Laurie & Clarissa

Karen & Lukas & Nancy

Betsy & Colette

Victoria & Sara

Cynthia & Andria

Marcy & Carolina

Sharon & Justin

Sharon & Coleen

Sharon & Christopher

Uli & Michelle

Victoria & Galen

Keith & Katherine

Jennifer Kenyon, PhD

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, U.S. Department of the Interior

Pursuit and Decay

Jennifer Kenyon, PhD, works for the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in the U.S. Department of the Interior. She was part of the MIT-WHOI Joint Program while she was working towards her degree, during which her research involved tracing carbon and other elements in the ocean by using an unusual tool: radioactivity. By using radioactivity, she was able to learn more about how carbon particles move in the ocean. This sort of research can help answer important questions that aid in understanding how the ocean stores carbon in the face of climate change, such as: How much carbon enters the ocean? Where does it go? How long does carbon stay in the ocean?

Laurie Kaplowitz is a painter and retired Chancellor Professor Emerita from UMass Dartmouth where she taught painting and drawing. Their decision to create a graphic story book arose from a mutual interest in narrative story-telling and graphic novels. Jennifer has written the text based on her research and geared to a young adult audience. Laurie has created imagery that literally embodies these somewhat abstract and non-visual concepts and natural forces. Together they tell a story of how carbon cycles through our oceans.

Both Laurie and Jennifer are committed to education and outreach, and as such wanted to create a digestible graphic story that could serve both as an art piece and a learning tool. Their project visually explores, through the eyes of an ocean scientist, the journey of carbon particles from the surface ocean to the deep ocean and the subsequent “chase” of radioactivity in pursuit of carbon.

keith Prue

Elected Artist Member of Art League RI, and an Exhibiting Member of the RI Center for Photographic Arts

Bloom

Keith Prue is a substantially self-taught artist, often presenting multiple adjacent images in a frame, for visual impact or to draw contextual comparison. From living and working on four continents and visiting more than fifty countries, he explores and contrasts cultural nuances. Exhibiting online and showing in group exhibitions, his photographs are held in private collections in the USA and elsewhere. He is an Elected Artist Member of Art League RI, and an Exhibiting Member of the RI Center for Photographic Arts.

Suzanna (Suzi) Clark is a recent graduate of the MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program, where she researched Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs), also known as red tides. HABs are the rapid growth of microscopic algae, which can sometimes be toxic to humans or threatening to other marine life. Suzi’s research focused on trying to explain these blooms through a variety of techniques, including collecting bottles of ocean water and running complex computer models. She is particularly interested in the human-science interface, which is why she was drawn to this project that is motivated by connecting the oceans and human health. She has recently moved away from the ocean but continues to work at the human-science interface, helping Minnesotans to adapt to climate change.

Caroline Ummenhofer, PhD

Associate Scientist, Department of Physical Oceanography, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Marine Heatwaves

Deb Ehrens is a lens-based artist creating contemplative and painterly imagery. Her award-winning work has been exhibited regionally and nationally. Deb lives in Dartmouth, MA and is a Juried Artist Member of the Cape Cod Art Center, Exhibiting Member of the Rhode Island Center for Photographic Arts and Elected Member of the Art League RI.

Svenja is a research associate in the Physical Oceanography department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She studied warm water transport toward ice shelves in Antarctica during her PhD but got interested in marine heatwaves due to their potential impacts and societal relevance. For her work Svenja utilizes many different tools and datasets depending on the research question; including ocean models, ship-based measurements, satellite data, data from marine mammals or floating robots that profile the subsurface ocean. Svenja always tries to keep the big picture in mind and to tell a story with her results.

Caroline is an Associate Scientist in the Physical Oceanography department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She focuses on understanding the ocean's role in the global water cycle, in particular extreme events like droughts and floods. Her interdisciplinary research combines data from global observations, computer simulations with environmental archives around the world, such as tree-rings across Southeast Asia, stalagmites in Australia and Portugal, Indian Ocean corals, bivalve shells in the Gulf of Maine, and historical data from ship logbooks and church records. A key goal of Caroline's research has been to bridge the gap between ocean and climate science and its impacts on society: she aims to provide practical outcomes of use to stakeholders and translate the implications of her research findings to the broader public.

chrissy herndandez, phd

Postdoctoral Associate at Cornell University and Guest Investigator at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI)

Drifters

Kathy Hodge attended RISD and has a BFA in painting from Swain School of Design. She has long taken inspiration from the natural world, exhibiting her work in many one person shows. She was appointed Artist in Residence in thirteen of our National Parks and Forests, most recently in Denali National Park, and was awarded the Fellowship in Painting from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts in 2017. She is an Elected Artist Member of the Art League RI.

She is excited to be part of the Synergy II project, and hopes to have viewers become intrigued with what they might now know about ocean life, and how the creatures we may never see — the ‘drifters’ — are the basis of life as we know it, on so many levels.

Chrissy Hernandez joined the Synergy II project while pursuing her PhD at WHOI, which she successfully completed in October 2020. Her thesis work focused on the distribution, growth, and transport of larval (baby) fishes in the ocean, with a particular focus on larval tunas. When they hatch, these tiny fish do not even have fins yet, and, combined with their small size, this means that they are not very good at swimming. Chrissy studies field-collected samples of these fish to understand where and when they are most abundant, and extracts their tiny “ear-bones” or “otoliths” to investigate their age (in days) and growth. This work is important for understanding the population dynamics of these species, particularly when we are deciding how to manage harvested and protected populations. Fish produce millions of eggs each year, and less than 1% of these offspring will survive to 1 year of age-- this means that tiny changes in the survival of the earliest life stages can have a big impact on how many fish we can catch a few years down the line!

Hong Xu, PhD

Amateur Photographer/Digital Artist, Member of Art League RI

Caroline Ummenhofer, PhD

Associate Scientist, Department of Physical Oceanography, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

From Sea Salt to Rainfall

Hong Xu is an amateur photographer/digital artist. Caroline Ummenhofer is a research scientist and a faculty member at WHOI (Woods Hole Oceanography Institution). They collaborate to create an art project that will convey the ocean’s role in the global water cycle; more specifically to showcase new research findings how salinity levels at the ocean surface might help predict rainfall on land.

Sujata Murty, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York

Oceans of Time

Marcy Cohen studied art and photography at the School of Visual Arts, the International Center of Photography and Maine Media. She is an Elected Artist of the Art League RI, Exhibiting Member of the Rhode Island Center for Photographic Arts, Praxis Gallery and the Colorado Photographic Arts Center. Her photographs have been exhibited in galleries nationally and internationally and online on Artsy and online publications such as F-Stop and the Curated Fridge. Later this year her work will be exhibited in the Seventh Edition of Eyes on Main Street and Tales of the Unwritten during the Trieste Photo Days. Marcy also serves as a member of the Board of Directors of the Cue Art Foundation, a not-for-profit contemporary art space in New York City dedicated to creating career and educational opportunities for emerging artists. She is also an attorney licensed to practice law in the State of New York and currently serves as Chief Legal Officer for ING Americas.

Sujata Murty is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences at the University at Albany. Her research focuses on understanding past changes in climate and ocean systems to improve our ability to anticipate future changes in a warming world. To do so, she synthesizes observations, climate, and ocean model simulations, and geochemical data from climate archives including corals from the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions and tree rings from Southeast Asia. Overall, Sujata aims to fill in the gap in documenting human-induced climate change that existing instrumental climate records cannot resolve. She is also passionate about finding creative ways to more broadly communicate her research and the impacts of climate change through art-science collaborations.

The photographs in this series, Oceans of Time, are composites that include elements from Sujata’s dives in the Indonesian Seas and Pacific Ocean, layered in a colorful, dreamlike melody with other images of time and the underwater world. Corals are known for longevity. An individual coral can in certain cases grow continuously for hundreds of years at a time, acting as a meteorological weather station in the ocean that records changes in climate and environmental conditions. Art and science generally operate in separate silos. We believe creating more synergy between art and science will instill greater understanding allowing scientists to reach broader audiences and instill wide-ranging intellectual and emotional connections to their work. Our intent is to create work that displays an optimistic future realized through a constructive collaboration between science and the forces of nature.

Ellen Biegert

Freelance Artist, Landscape Architect, Elected Artist: Art League RI

LaRRY J. Pratt, PhD

Senior Scientist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Turbulence

Larry Pratt is a physical oceanographer who carries out research on the physics of ocean circulation and climate. Over the past 30 years he has taught numerous courses at MIT on ocean dynamics and is co-author of a book on the ocean abyssal circulation. Larry has pursued many collaborations on the art/science interface and has co-taught classes at the Pasadena Art Center College of Design, Boston Conservatory, and MIT on physics, dance, and the artistic representation of scientific data. In addition to his work with Ellen on ocean mixing and turbulence, he is currently engaged in a project on the impact of sea level rise with Boston Dance Theater.

Ellen Biegert is an Artist and Landscape Architect who focuses on combining creativity and design with the environment. Inspired by nature and its interwoven systems, she looks to strengthen the innate connection humans have with the natural world through both art and landscape. Working with Larry on the Synergy II project has created the opportunity to strengthen the bond between individuals and the ocean.

Jing He

PhD Candidate at MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program

Submesoscale soup

Janine Wong is a designer and artist who received her MFA from Yale School of Art. She researches color and hybrid print processes combining both traditional techniques and digital technologies. She explores the intersections between design, printmaking and book arts and employs the results of this research in her own artist books, prints, and collages. Janine’s current research is in color theory, looking at the history of color theory and bringing past concepts to current practice.

Jing He is a scientist and PhD candidate at MIT and the Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution where she studies physical oceanography to better understand the ocean’s role in climate change. She researches how ocean currents in “submesoscale soup” transport nutrients to support life in the ocean and helps the ocean sequester carbon dioxide. To do this, she employs a range of tools ranging from making direct measurements off research ships, to running numerical ocean simulations on computers, and utilizing machine learning to find patterns in large data sets.

This collaboration showcases the beauty of the rich and unseen ocean physics that is central to Jing’s research in an engaging and accessible way. In this artist’s book, Jing and Janine use cooking analogies to break down a complex “submesoscale soup” of currents down into its essential ingredients and steps, with each step beautifully illustrated with marbling to help readers imagine how different physical phenomena combine to create the complex ocean.

Noah Paul Germolus

PhD Candidate, MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography

Visualizing the Unseen: Cellular Metabolites in Ocean Ecology

Noah Paul Germolus is a PhD candidate studying Chemical Oceanography. His research seeks to bridge the gap between two forces that compete for essential molecules in the upper ocean: the microbes that produce and consume these nutrients, and the ambivalent mechanisms of chemistry that alter or destroy them.

Heather Stivison is an award-winning artist whose work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in universities, galleries, and museums. Originally from New Jersey, Stivison is a former museum director who has also served as the president of both the New Jersey Association of Museums and the Mid-Atlantic Association of Museums. She is a published author and a recipient of an art history research grant from the Arts & Crafts Research Fund. She holds an MFA in painting from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

Saberah Malik

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

Max Jahns

PhD candidate in microbial oceanography at the MIT-WHOI Joint Program

Forms of Every Breath You Take

Saberah Malik is an accomplished visual artist with expertise in textiles who teamed up with Max Jahns, a PhD candidate in oceanography at the MIT-WHOI Joint Program who studies the interactions between living things in the marine environment, and their importance for the health of our planet. “Forms of Every Breath You Take” showcases the awe-inspiring forms, and the unsung importance of phytoplankton in the world’s oceans. In many ways, these creatures are the lungs of our planet, producing over 50% of the world’s oxygen. “Forms of Every Breath You Take” aims to celebrate these life-sustaining heroes of the microbial world. Our project addresses morphology, which is the study of form and function. The project’s use of transparent, flowing fabrics and luminescent dyes illustrates the most important aspects of phytoplankton morphology - light, color, and configuration- which have been refined over billions of years. The creatures you see before you are all made entirely of fabric but are representations of real microscopic organisms you could find in any drop of water, all of which are responsible for life as we know it today.

Nina Whitney, Phd

NOAA Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Fellow at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

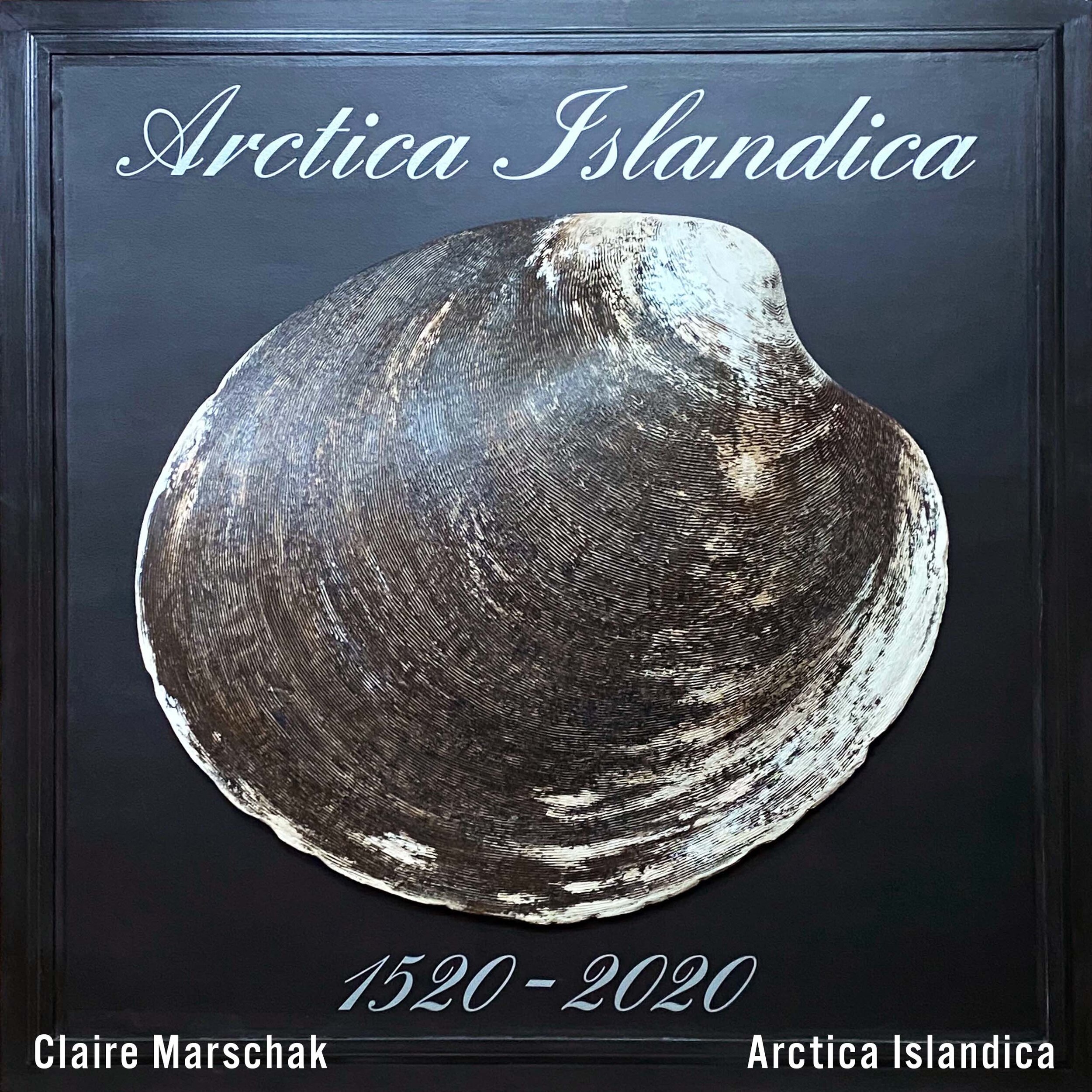

Arctica Islandica

Claire Marschak is an artist and designer who has teamed up with Nina Whitney, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow whose research focuses on understanding past ocean conditions. Their project tackles the topic of paleoceanographic reconstructions: that is interpreting changes in past ocean conditions using biogeochemical materials, in this case the chemistry in clam shells. This project presents a painted relief sculpture to showcase the elegance of these seemingly humble clams and all that they can teach us about our past world. The goal of Arctica Islandica is to increase understanding of how we know what we know about past ocean conditions as well as put the human experience into a much broader environmental history.

cynthia didonato

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

Michelle Hauer

PhD Candidate, URI Graduate School of Oceanography

Animating the Deep sea

Cynthia DiDonato — The beauty of deep-sea hydrothermal vents lies in their surreal landscapes and the unique creatures that call them home. These vents are often surrounded by towering chimneys, formed from mineral deposits precipitated out of the superheated water that gushes forth from the seafloor. These chimneys can be adorned with vibrant hues, created by the diverse array of microorganisms and chemosynthetic organisms that cling to their surfaces. Despite the extreme conditions—high temperatures, acidic waters, and toxic chemicals—these vents support dense populations of strange and alien creatures, such as giant tube worms, eyeless shrimp, and ghostly octopuses. This is in sharp contrast to much of the rest of the deep ocean, which lacks nutrients and therefore tends to be sparsely populated. Harnessing the power of visual art to showcase the beauty and ecology of deep sea hydrothermal vents can be a potent tool for inspiring people to learn about and protect these remarkable habitats. By translating scientific knowledge into artistic creations, we can bring these remote and inaccessible environments to life, allowing people to connect with them on a visceral level.

Michelle Hauer — My research centers on the population genomics of microbial symbionts from endangered and vulnerable deep-sea hydrothermal vent animals. I investigate how environmental variables, like geochemistry, viral infection, and microbial lifestyle shape symbiont population structuring. Broadly, I am interested in the murkiness of thresholds, or concepts that challenge our traditional notions of dichotomies – questioning things like species concepts (e.g., whether – or how – a “species” should be treated as a discrete or continuous concept), what makes something a mutualist or a pathogen (qualities that have more in common than we traditionally appreciate), and when we should consider associations in nature as symbioses versus a single functioning unit.

clarissa karthauser, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow, WHOI

“Page 1, Birth,” “Page 2, Awakening,” “Page 3, Splitting,” & “Page 4, Blue Eye”

“Birth” — Laurie Kaplowitz

“Awakening” — Laurie Kaplowitz

“Splitting” — Laurie Kaplowitz

“Blue Eye” — Laurie Kaplowitz

Laurie Kaplowitz — These paintings and text images represent the first 4 pages of Marine Snow, A Lyric Meditation, which will be a book of paintings accompanied by text that traces the journey of marine snow as it travels from the surface of the ocean to the sea floor. Karthauser’s scientific work combines biochemistry with microbiology to gain a deeper understanding of carbon cycling in the ocean and the processes that drive it.

We both liked the idea of envisioning marine snow as a woman and personifying the life cycle of organic matter as it travels from the ocean’s surface to the sea floor. Kaurthauser wrote the narrative and designed the text pages. The narrative, a meditation that is lyric and elegiac in tone, accompanies my paintings to evoke birth, growth, and eternal sleep. I have incorporated organic matter – dried flowers, leaves, and seaweed into the painted imagery and compositions just as organic matter is blown onto the ocean’s surface and begins its journey to the sea floor, sequestering carbon and helping to keep the planet in balance.

lukas taenzer

PhD Candidate, MIT-WHOI Joint Program

nancy tucker

Composer

aqua turbulentum

Karen LaFleur — “Aqua Turbulentum” expresses eddy movements (small whirlpools) that intermingle along shelf-break boundary zones between coastal waters and the open ocean just south of Cape Cod. This moving image artwork is inspired by the studies of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientist Lukas Taenzer.

Karen LaFleur fills “Aqua Turbulentum” with invented sea-creatures, data-collecting robots, and swirling water movements to imagine Taenzer’s scientific studies in how the coastal and open ocean intermingle and mix with one another by following ocean salinity, temperature, and current signals. The data collected expands our understanding of ocean waterbody dynamics and sheds light on the contribution of eddies to the overall health of our oceans. “Aqua Turbultentum’s” visual beauty and musical interpretation casts a sense of intrigue over these important studies and brings to life eddy dynamics that lay hidden beneath the ocean surface.

Karen LaFleur is a Techspressionist (Techspressionism is a 21st century artistic and social movement in which technology is utilized as a means to express emotional experience) artist, writer and moving image animator. Her work explores the interplay between interior and exterior worlds with a focus on adaptability. She reveals vulnerabilities in complex relationships and highlights resiliencies in these ever-shifting landscapes.

Motion is an integral part of her creative process whether digitally rendered or traditionally captured. Her pencil drawings on vellum form a base for her moving image works and include the tiniest of details. Each piece is then digitally painted in a variety of applications. Her skill in visual storytelling combined with Nancy Tucker’s narrative music, brings her moving image works to life with a fluidity of gesture and story rhythm that enriches the work’s believability.

Karen LaFleur’s fascination with the ocean began as a child living by the ocean and traveling inter-tidal waters in her small boat. Unhindered by parental constraints, she was free to discover and observe nature first-hand. Today the ocean’s ecosystems and current dynamics still influence her work.

Resume Includes: Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington DC, Fuller Museum MA, Union Square San Francisco CA, Hudson Valley MOCA NY, MOCA L.I.ghts NY, Cotuit Center for the Arts Video Wall MA, Cape Cod Museum of Art MA, and the Southampton Art Center NY, The Wrong Biennial, Kingsborough Art Museum, Brooklyn NY.

“Aqua Turbulentum” (detail) — Karen LaFleur

“Aqua Turbulentum” (detail) — Karen LaFleur

Nancy Tucker — I love to write music and I’ve had my sights set on writing for visual art for a long time. When Karen first asked me to compose for her animations I was thrilled. And as more people requested music for their projects, my opportunity to explore composing for moving images expanded.

The process of writing for animations…It is a matter of feeling it…trying to feel what it is an artist is trying to get across, and also getting the rhythm right so that when images appear, there is music that coincides with whatever is coming into frame. Artists and videographers sometimes just send me still pictures … and from that I really get a sense of what it is they are trying to do with an animation. Sometimes we are working in our separate corners, and when we put the music together with the visuals, it just works and it’s magic.

Lukas Taenzer — Taenzer studies Ocean and Climate Physics while pursuing his PhD at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, MA, U.S. He is fascinated by how waters of coastal and open ocean origin intermingle and mix with one another. Through his work, he strives to improve our understanding of how water exchange processes between the open and the coastal ocean affect coastal ecosystems and communities in New England through climate change. As a seagoing oceanographer, Taenzer combines data from a variety of sources: measurements from research vessels, ocean robots, moorings, satellite images, and ocean models output. He follows temperature, salinity, and ocean current signals in the water to identify cases for when open ocean water mixed with coastal ocean water and changed coastal ecosystem conditions. Lukas’ work has brought him onto research cruises in the Northwest Atlantic and in the Arctic Ocean.

Working together with Techspressionist artist Karen LaFleur allows Taenzer to bridge the gap between what we already know about the oceans from roughly 120 years of research, and the signals he finds in the data today. Observing the earth is not a carefully controlled science experiment in which all but one variable is eliminated and is repeated many times. Instead, we only have one earth to conduct experiments on, and all ocean and atmospheric processes operate at the same time. Taenzer’s mooring and ocean robot might not be placed at exactly the right spot in space and time to identify one of the highly localized and turbulent ‘exchange’ events where open and coastal waters swapped places. In contrast, circumstantial evidence is typically much easier to observe, and it encourages earth scientists to come up with creative ways to learn more about the earth from our data. In combining the dots between evidence in the data and the shadowy ‘exchange’ process in question, art can help!

betsy ritz

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

colette kelly, Phd

Postdoctoral Fellow, WHOI

cyclonic flux & argo floats

“Cyclonic Flux” — Betsy Ritz

“Argo Floats” — Betsy Ritz

Betsy Ritz — Scientist Colette Kelly, PhD, and I have worked together to express artistically their work on the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O) in the Southern Ocean.

In the first piece I created, “Cyclonic Flux,” I tried to suggest the flux of nitrous oxide coming out of the low pressure center of a revolving Southern Ocean cyclone. I made a papier-mâché bowl from recycled newspaper and worked to make it resemble a storm or cyclone with ocean waves, and placed it on a revolving platform that viewers can gently push to simulate the cyclone’s swirl. Dr. Kelly provided me with a barometric pressure map that showed in different color bars the varied air pressures of a cyclonic storm, and I painted that on the bottom of the cyclone bowl. The lowest pressure area, painted dark blue, is where Dr. Kelly’s current research found the most nitrous oxide emerged from, and in this piece, the molecules, made of one red oxygen atom bonded to two blue nitrogen atoms, spring out from that center.

In the second piece, “Argo Floats,” I tried to include three different concepts in one piece, based on information I learned from Dr. Kelly and their nitrous oxide research. I created a large paper mache bowl that was painted in layers to suggest different depths of the ocean, with a large part of the ocean being without light, painted darker shades of blue. The yellow wood strips perched at different levels inside the bowl suggest the movement of Argo floats, the robotic floats that move up and down through different layers of the ocean to collect data, and then surface to radio that data to satellites. The top inner rim of the bowl contains data ocean scientists have collected showing how the amount of nitrous oxide has increased since it was first measured in 1977 until 2023—increasing approximately 10 percent. The ocean itself is represented by the bowl, reminding us that though we think of the ocean as endless, it is in fact finite.

Dr. Kelly’s work and the work of other WHOI scientists help us understand how climate change affects the ocean, and vice versa. I used art materials like paper mache made from recycled newspapers and glue from flour and water in an attempt to be mindful of art’s impact on the environment and climate change.

Colette Kelly, PhD — Colette Kelly graduated in 2017 from Barnard College of Columbia University, where they double majored in Dance and Environmental Science. In 2023, they received their PhD from Stanford University in Earth System Science. They are now a GO-SHIP Postdoctoral Fellow at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The Southern Ocean is a vast, essentially uninterrupted ocean that encircles Antarctica. Because there are no continents to impede their motion, intense storms develop over these frigid waters, gathering energy from the winds, ocean currents, and temperature contrasts between warm and cold waters. The swirling motion of the winds diverts the air outwards from these storms, creating pockets of low atmospheric pressure in their centers. Sampling the ocean within such storms from a ship is impossible, due to the ferocious winds and towering waves. But what oceanographic phenomena are we missing in our inability to collect samples from within them?

Of all the greenhouse gasses, nitrous oxide is one of the most potent, yet the most poorly understood. Its capacity to warm the atmosphere, on a per-molecule basis, is 300 times that of carbon dioxide. This means that one molecule of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere has the global warming potential of 300 molecules of carbon dioxide. Scientists know that the ocean emits nitrous oxide to the atmosphere, but because the processes that affect nitrous oxide emissions are so complex, we still do not fully understand how much nitrous oxide comes out of the ocean and into the atmosphere. This is especially true in places where, and at times when, collecting samples to measure nitrous oxide is impossible — such as the middle of a Southern Ocean storm.

In this study, we used special robots called Argo Floats to simulate nitrous oxide fluxes in the Southern Ocean. Because the floats are fully autonomous — they do not require a human to direct them — they can collect data even in the most inhospitable environments, including cyclones and underneath the ice. By analyzing the simulated nitrous oxide data from these floats, we discovered that the Southern Ocean is a much larger source of nitrous oxide than we previously thought. This is because the low atmospheric pressure in the centers of these storms essentially sucks the nitrous oxide out of the ocean and into the atmosphere. Once it is in the atmosphere, the nitrous oxide can and will trap heat and contribute to global warming. This can offset some of the carbon dioxide that the Southern Ocean absorbs. In essence, by looking beyond what we can do with shipboard data, we found out that the oceans around Antarctica are both source and sink of greenhouse gas to the atmosphere.

victoria guerina

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

sara gonzalez, phd

Postdoctoral Scholar, WHOI

resilience in a warming ocean

“Resilience in a Warming Ocean” — Victoria Guerina

Victoria Guerina — Sugar kelp (Saccarina latissima) is a commercially important, edible kelp. It can also be used as a sweetener and as a biofuel. It grows in cold ocean water and is farmed along the northeast and northwest coasts of the USA and in other parts of the world. As ocean temperatures rise, we are searching for genetic variants that can thrive in warmer waters. This artwork, made of dried kelp and cotton fiber, represents a healthy heat tolerant variant and the more common heat intolerant kelp that turns white and disintegrates as the oceans get warmer. The artwork is in the process of completion.

“Resilience in a Warming Ocean” is based on Gonzalez’s work with sugar kelp. She is looking for variants of a kelp that normally grows in cold water that will thrive in warmer water temperatures. I initially wanted to create paper using the kelp, but found it was very difficult to work with. The kelp really has its own character and resisted any attempts to make it do what I wanted. After several months of trials, I was able to create a version of both cold and warm tolerant kelp using dried kelp and paper fiber.

cynthia beth rubin

Visual artist

Andria Miller

M.S., Menden-Deuer lab, URI Graduate School of Oceanography

sensual data

“Salinity, Chlorophyll, Temperature, State I” — Cynthia Beth Rubin

“Salinity, Chlorophyll, Temperature, State II” — Cynthia Beth Rubin

“Nutrients and Heat” — Cynthia Beth Rubin

“Plankton Abundance, Silicate, Salinity, and Temperature” — Cynthia Beth Rubin

Cynthia Beth Rubin — Scientist Suzanne Menden-Deuer and I use a Techspressionist (Techspressionism is a 21st century artistic and social movement in which technology is utilized as a means to express emotional experience) approach to blending oceanographic research with artistic interpretation, providing a new method for conveying environmental data. We constructed the imagery by analyzing data from Narragansett Bay, a marine estuary that is crucial to Rhode Island’s fishing, recreation, and local economy. Results were then graphed as curved lines, and the forms created by these data graphs treated as abstract forms in expressive layered artwork.

Microscopic plankton, both photographic and hand-drawn, are integrated into the artworks, giving context to an important reason for paying attention to the changing environment. Often overlooked due to their invisibility to the naked eye, plankton play a crucial role in sustaining life on Earth. Plankton are at the bottom of the food chain, and they produce a significant portion of the oxygen we breathe. Without plankton, we could not survive.

Our imagery, which is both sensual and informative, invites scientists, visual thinkers, and the general public to contemplate the changes in an environment over a year.

I. In this first Techspressionist image, combining the elements of chlorophyll, salinity, and temperature, the data is layered. In true expressionist fashion, the red cubes of salt in the lower front call to the reds at the peak of the temperature curve, and cube forms call to the salt in the salinity layer. The soft green ripples of chlorophyll clearly continue throughout the season. The vital marine life of plankton diatom chains hang above it all, as in the ocean they form the basis of all production and food webs.

II. In this iteration the frame from the original graph reveals the months of the year and points on the Y axis. More readable to scientists as data mapping, the frame and color choices put the chlorophyll in a more prominent position, asking the viewer to imagine that the temperature and salinity graphs continue behind the rising chlorophyll of winter. This is a true reflection of the environmental dynamics, where temperature and salinity constrain which organisms can survive at those conditions.

III. Mapping the elements of phosphate and nitrite + nitrate presented a new challenge. These nutrients had to be interwoven, each with distinct colors and textures, to reveal their curves rise and fall through the year, while being strikingly similar for much of winter. An abundance of playfully placed plankton, including some that are hand-drawn, reminds the viewer of the living organisms inhabiting this marine environment. The excretion product ammonium was added as a compositional component to provide visual space between the nutrients and temperature, while also showing important data differences. An abundance of playfully placed plankton, including some that are hand-drawn, reminds the viewer of the living organisms inhabiting this marine environment.

IV. In this image we see the fluctuation in how many plankton are in the water throughout the year from weekly measurements, from February 2022 to February 2023. The image includes an overlay of the data graph with temperature and the concentration of the essential nutrient silicate to add another dimension to the graph. To show fine detail of plankton structures, the image includes composites of photographs of plankton taken with a scanning electron microscope. Abundances changes substantially through the year, and in the final weeks the quantity of plankton was so great that the number continues above and beyond the extend of the graph.

Carolina Camargo, Phd

Postdoctorate in Physical Oceanography at WHOI

The rising tides 1, 2, 3, & 4

“Rising Tides 1” — Marcy Cohen

“Rising Tides 2” — Marcy Cohen

“Rising Tides 3” — Marcy Cohen

“Rising Tides 4” — Marcy Cohen

Marcy Cohen – These photographs were taken in Death Valley and the Big Island of Hawaii and were inspired by Carolina Camargo’s, PhD, research on sea-level change.

Climate change is affecting the world in different ways, from droughts to floods, from heat waves to sea-level rise. Death Valley is the driest place in North America, receiving about 2 inches of rain per year. In 2023, Hurricane Hillary and an atmospheric river changed the situation, bringing almost 5 inches of rain in just 6 months. Kona Lows have been halting the Big Island’s renowned sunshine, drenching the tropical island with frequent bouts of prolonged heavy rains. While these are natural phenomena, they are becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change.

Another clear consequence of climate change is sea-level rise. In most coasts around the world, the sea-level is rising, and quickly. And while the rise and ebb of tides is a natural effect, the sea-level rise is bringing these variations closer to human settlements and infrastructures. Consequently, cities along the U.S. East coast experience flooding even without storms, simply due to above-normal water levels. Understanding how and why sea-level is changing in each region is fundamental to ensure the resilience of our coastal communities.

Camargo, a postdoctoral researcher at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, looks at different drivers of sea-level change on a regional level. For example, how much sea-level is rising because the oceans are getting warmer, or because ice from glaciers and ice sheets are melting, or how the movement of ocean currents affect sea level. It is important that we understand all of these mechanisms, so we can get reliable and robust projections of future sea levels, and keep our coasts protected.

Marcy’s images poignantly demonstrate the powerful impact of rising seas and climate change on our environment and the human experience.

sharon cutts

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

justin sankey

PhD Candidate, URI Graduate School of Oceanography

mermaid in kelp

“Mermaid in Kelp” — Sharon Cutts

Sharon Cutts – “Mermaid in Kelp” is a painting in response to URI graduate student Justin Sankey’s research on the effects of PFAS in marine organisms. PFAS (short for per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are chemicals created to enhance consumer products, such as Teflon coatings and for treatments for stain resistance and fire retardance. These chemicals are extremely long lasting, and rather than breaking down in the environment, they persist and find their way into our water and food supply.

Justin’s research has shown that PFAS in the ocean are particularly absorbed by kelp, which is in turn fed upon by a wide spectrum of marine life. Some of these PFAS have been linked to cancer and the EPA has said that there is no safe level of exposure to them.

In my painting, the kelp is speckled and pocked with the PFAS that it has absorbed from the ocean which has been polluted by runoff and sewage. The mermaid is also speckled with these pollutants. And when we eat animals that have eaten kelp, we too end up with PFAS in our bodies.

Justin Sankey – Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a man-made class of persistent organic pollutants, so called “forever chemicals” that are ubiquitous in the environment. Common sources of PFAS include, but are not limited to, fire suppressant foams, non-stick coatings, water/grease/stain resistant coatings for textiles, food packaging, and cosmetics. Several types of PFAS have been found to be carcinogenic and/or endocrine disruptors that have a negative impact on public health around the world.

Graduate researcher, Justin Sankey, is a PhD student at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography and a National Institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS) Trainee at URI’s Sources, Transport, Exposure, and Effects of PFAS (STEEP) Superfund Research Center. Justin’s research focuses on the potential impact of PFAS on the emerging kelp farms of Rhode Island. Their research focuses on characterizing the bioaccumulation potential of PFAS in kelp through a mix of laboratory and field-based studies. Preliminary results suggest that kelp has higher than expected potential to accumulate PFAS in its tissues (i.e. kelp possesses a high bioaccumulation potential); however, further analysis and validation is needed to verify these results. The results of these studies may show that kelp can be used as a co-crop with other aquaculture, such as oysters, to help reduce PFAS concentrations in the more profitable crop. Additionally, if kelp is to be used for consumption or as biosolid applications to farm fields, this data may aid in establishing water quality standards to mitigate potentially high concentrations of PFAS in the kelp crop and inform the locations of future water leases in Rhode Island.

sharon cutts

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

coleen suckling, PhD

URI Associate Professor in Sustainable Aquaculture

sea urchin: out of water

“Sea Urchin: Out of Water” — Sharon Cutts

Sharon Cutts — “Sea Urchin: Out of Water” was inspired by URI research Professor Coleen Suckling and her work to promote commercial aquaculture of the purple sea urchin for restaurant tables in Rhode Island.

Sea urchins are hardy and in some circumstances they can help other organisms by eating excessive algae. But they can also over-populate and scour the ocean floor, negatively impacting other ocean life. Eating them would be a good solution according to Professor Suckling.

What particularly attracted me to Professor Suckling’s research is my memory of a beautiful bay in Jamaica from 40 years ago where there was nothing left but black sea urchins studding the ocean floor. No shellfish, no fish, no vegetation. Just urchins. A desolate scene. When I saw one of Professor Suckling’s articles suggesting aquaculture of urchins, I thought: What a good idea! Let’s eat them.

This sculpture is made of rigid painted canvas, stiffened by multiple coats of gesso and acrylic paint. It is covered with staples to duplicate the spines that cover sea urchins.

Coleen Suckling, PhD — Professor Coleen Suckling has been working in the field of sea urchin research and production since 2005 having worked on multiple species across the world. Since moving to the US from the UK in 2018, she has been working on sustaining the sea urchin industry across New England by developing projects to optimize how we produce sea urchins in aquaculture, helping growers experiment with growing sea urchins and increasing awareness that they are an edible option for seafood.

sharon cutts

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

christopher lane, PhD

URI Professor in Biological Sciences

underwater

“Underwater” — Sharon Cutts

Sharon Cutts — Life is complicated, especially the closer you look, and the inspiration for my painting UNDERWATER was the intricate research by University of Rhode Island biology professor and researcher Christopher Lane. His research has broken new ground in the examination of the single-celled organisms that help to break down waste in the guts of filter-feeding sea squirts—tunicates that live along the eastern seaboard. Their water-filled sac-like bodies with two tubular openings draw water in and out to extract plankton.

Professor Lane’s research has shown that the microscopic organisms in the renal systems of tunicates likely began as one of a large family of one-celled parasites. The interesting question is: how did it transition from a parasite, which harms its host, to something that helps eliminate the host’s waste? This question is still being examined.

As an artist, I was inspired by Professor Lane’s research to paint an inter-tidal swirl in shades of blue. Various tunicates are depicted as brown, blue and gray bagpipe-like structures scattered here and there. All these organisms live in a rich and chaotic churning of the inter and sub-tidal ocean.

The black rectangle in the center continues the swirling patterns and takes my artistic expression outside of Professor Lane’s research to connect to a potential future of an ocean going black.

Christopher Lane, PhD — Like a lot of kids, Chris grew up wanting to be a marine biologist and turned out to be just stubborn enough to make it happen. After doing a PhD using DNA to determine how different algae were related to one another, he did a postdoc on the topic of ancient symbiosis, which fuels his research approach today at URI. His lab currently works to identify changes in the genomes of organisms as they transition from free living to parasitic life cycles, or become free living from parasitic ancestors.

The work depicted in the painting is a project involving many biological partners. Tunicates, or sea squirts, are the hosts in this system to an unusual lineage of apicomplexans. Better known as the causative agents of human diseases like Malaria and Babesiosis, the apicomplexans in these tunicates appear to have no effect on the tunicate host. Rather than scavenge vitamins and metabolites from their host, these apicomplexans have instead taken in bacterial endosymbionts as internal factories for important biological building blocks. In doing so, they only need their tunicate host for a place to live and waste product to use as food, changing the dynamic of the relationship from parasitic, to commensal.

uli brahmst

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

michelle hauer

PhD Candidate, URI Graduate School of Oceanography

forged by Fire: Journey into the Depth of Hydrothermal Vents

“Forged by Fire: Journey into the Depth of Hydrothermal Vents” — Uli Brahmst

Uli Brahmst — I am a mixed media visual artist of German descent living in RI for the past 15 years. My affinity for nature and the urgency of the environmental crises have made me increasingly interested in environmental issues, especially in those that confront our local context. The relatively relaxed public stance towards environmental issues is alarming to me. Like art, the natural world is full of beauty and mystery. Some aspects of the miracles of nature are hidden from the bare eye and need to be made visible for a larger audience to appreciate them. Scientists and artists alike are driven by the curiosity of what lies behind the known. In their quest for discovery they observe, imagine, record, and pursue continuous problem solving. Making the abstract visible is central to many creative practices. My art is steeped in drawing and observation of abstract dynamics. I am interested in putting these skills in the service of science to make scientific knowledge more easily understandable to the broader public and to all ages. I am a quick learner and a deep thinker, I work comfortably in teams or on my own, and I am genuinely driven by curiosity. I am interested in that which is new and how we can connect it to the familiar with the goal to make it accessible and relatable. I move freely between visual modalities such as drawing, photography, fiber, and ceramics. With this flexible toolbox I can well imagine tackling a variety of scientific themes and to make their intrigue visible and engaging. This installation in particular is inspired by Michelle Hauer’s scientific work surrounding hydrothermal vents.

victoria guerina

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

galen wilcox

PhD Candidate, MIT-WHOI Joint Program

Antarctic Bottom Water at Two Scales

“Antarctic Bottom Water at Two Scales” — Victoria Guerina

Victoria Guerina — There are many factors which influence the behavior of ocean currents. Steep slopes and troughs on the ocean floor near Antarctica are dominated by a cascade of salty, cold, and dense water formed as a byproduct of sea ice freezing at the surface. This gravity-driven flow is also affected by surface winds and the rotation of the Earth, and occurs over scales of hundreds of kilometers, moving massive amounts of water. The energy involved is almost incomprehensible, and it feels like such an awe-inspiring process should be immune to the influence of human activity.

But as our planet warms, the physical factors which control these powerful Antarctic coastal flows are changing, and scientists are working to understand how the ocean will respond. The dense outflow of water from coastal Antarctica may be compensated by warm water from offshore that accelerates the melting of ice shelves. In this project we would like to demonstrate how complex bathymetry (the shape of the ocean floor) guides the flow of dense water, and explore the broader concepts of inevitability and change. We seek a balance between these educational and artistic goals.

We constructed a regional model with representations of the ocean floor in coastal Antarctica from paper relief, and used alcohol ink to track the flow of dense water through troughs, down slopes, and around seamounts. The flows in our regional model are both controlled and uncontrollable, governed by gravity but also chaotic and hard to predict. Small variations in the placement and quality of ink can lead to dramatically different results, or not much change at all. Our box model is a three dimensional, zoomed-in view of ocean circulation in coastal Antarctica made from paper and alcohol ink. The box model illustrates sinking cold plumes from the formation of sea ice, horizontal flow of warm water at greater depths, and the whorls of turbulent mixing between these water masses.

Antarctic Bottom Water at two scales came from looking at Wilcox’s work from two approaches. I was intrigued by the creation of cold, dense water by ice forming on the ocean surface. This “heavy” water falls to the bottom and creates ocean currents. As oceans become warmer, warm circumpolar water can flow in under the plumes of cold dense water disrupting the currents and possibly causing ice melting. I made a box model of this idea with a cast paper ice shelf and paper sides using alcohol inks to represent the different water temperatures and their movement. Galen was also interested in exploring the currents at a larger scale and so we created an ocean bottom (bathymetry) map and by applying alcohol inks we hope to see how water might flow based on the shape of the ocean floor and gravity. It has taken a good bit of time to find the best way to make this work so that the idea comes across as well as making an interesting piece of artwork. The work displayed here is still in progress as we continue to refine our methods for applying ink and color.

keith prue

Visual artist, elected artist of ALRI

katherine squires

PhD Candidate, MIT-WHOI Joint Program

plume

“Plume” — Keith Prue

Keith Prue — Inspired by Katie Squires’ research on hydrothermal vent fluids and their impact on ocean chemistry, this artwork comprises a composite of almost 600 images captured in the local environment.

Discovered in 1977, hydrothermal vents are essentially underwater hot springs that form at tectonic boundaries over 8,000 feet below the ocean’s surface. When vent fluids emerge from the seafloor, they deliver high concentrations of metals (e.g. iron and manganese) to the deep ocean. Eventually, these metals settle from the water column and are deposited on the seafloor. Squires, a graduate student at MIT and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, uses chemical patterns recorded in marine sediments to study where and how far hydrothermally sourced metals travel across the Pacific Ocean, and how this has varied over millions of years. Understanding how hydrothermal fluxes have changed through time is important because these fluids are a source of metals that marine organisms need to survive. Furthermore, many of these metals are used in renewable energy sources (e.g. electric vehicle batteries), and there is international interest in mining seafloor sediments to collect these metals for such purposes. It is important that we understand when, where, how, and at what rates these metals are deposited on the seafloor before undertaking actions that may impact hydrothermal vents, their deposits, and the organisms that depend on them.

Hydrothermal vents are complex geologic features and need specialist equipment to explore. Like all things oceanic, where it can take 10,000 years for the ocean floor to grow 1mm, they play a critical if not fully understood role in the ocean's ecosystem, with small changes leading to big and potentially irreversible consequences.